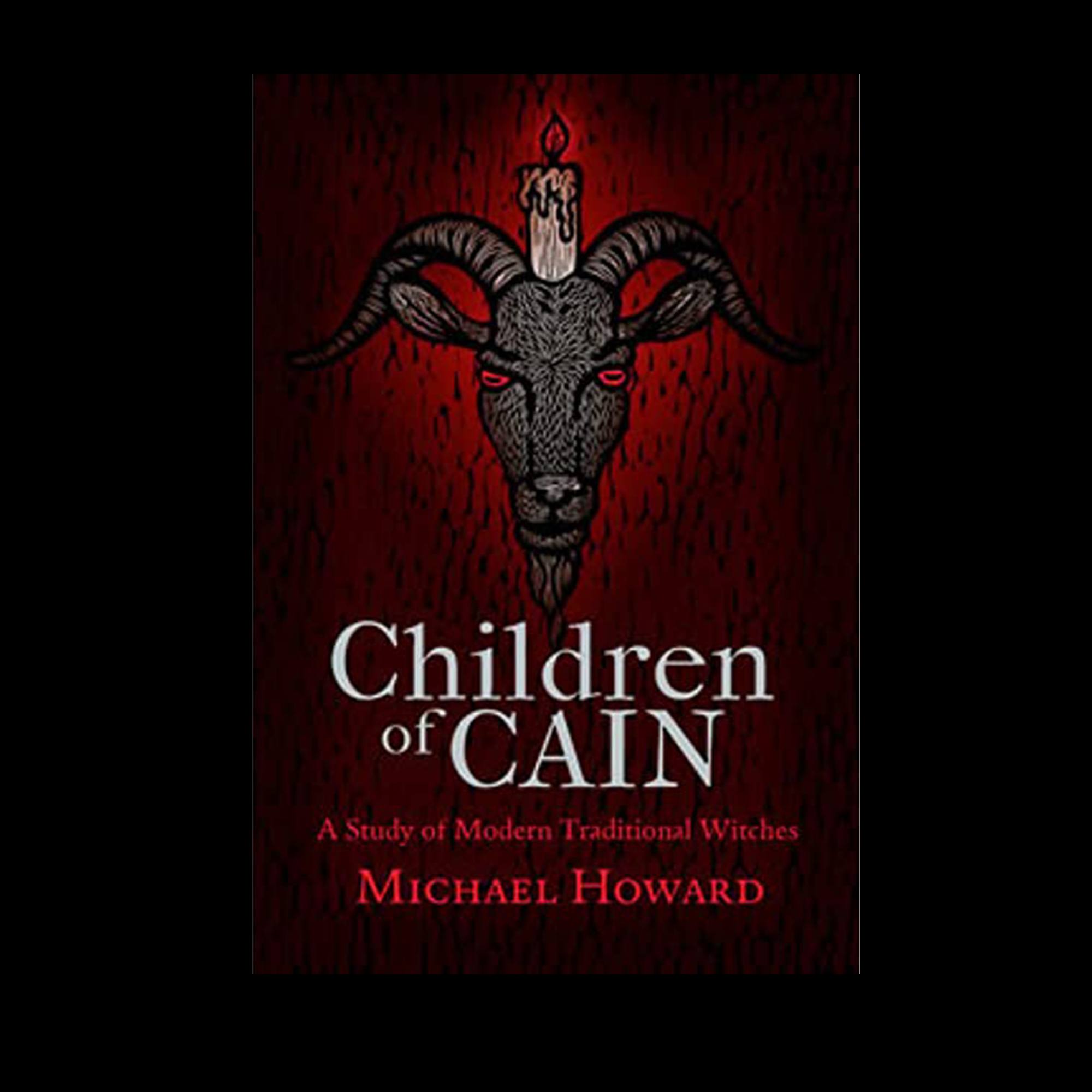

Children of Cain: A Study of Modern Traditional Witches

by Michael Howard

©2011 Xoanon Limited

Three Hands Press

317 pages

A Feri-Centered review by Storm Faerywolf

‘Children of Cain’ is an important book within the traditional witchcraft revival and one that is likely to be cited for years to come. In this work author Michael Howard presents a case for the survival of pre-Wiccan (‘traditional’) witchcraft, treating us to a look within several “covines” and groups that make the claims of pre-1940 lineages, the rough date when Gardner’s Wicca came on the scene.

Drawing from stories, first-hand accounts, and folklore, Howard presents us first with a general study of the traditional Craft, demonstrating differences between the neo-Pagan practices of the majority of modern Witchcraft and focusing on the former’s “more informal and improvised structure”, frequently based on older (and often fragmentary) rites and ceremonies. Howard presents ‘traditional witchcraft’ in terms that distinguish it from modern Wicca, such as the formers’ non-adherence to the Three-Fold Law, a differing vocabulary, or the tendency to not celebrate the Wheel of the Year (a modern creation not used in pre-Christian cultures). One interesting observance, according to Howard, is that many pre-modern groups tend to place focus on male deities rather than on the Goddess, which is generally the primary deity for modern witches.

Howard delves into specific traditions, individuals, and groups that have been influential to the modern traditional Craft revival. Individuals well known in traditionalist spheres such as Robert Cochrane and George Pickingill are given their due, and groups such as the Clan of Tubal Cain and the Regency are described in detail giving the reader a personal account of just how some of these groups operated and how they co-existed with each other. Other secret societies such as the Horse Whisperers (and their offshoot the Toadsmen) are also explored for connections to what has been called “Old Craft”.

The influence of these older groups are shown to have affected Gardner and his inheritance from the ‘New Forest Coven’, giving argument for threads of the ‘Old Craft’ being present and woven into the framework of modern Wicca. This theme of the old informing the new is a theme that is explored further in this book.

Of particular interest to Feri tradition readers is the chapter titled “American Traditional Witches”. About halfway into this section we are treated to an introduction to the late Victor Anderson, and even to a small bit of liturgy for ‘sealing the circle’ as well as some that purports to be from the initiation ceremony. Neither are core liturgies of traditional Feri (and a small deviation appears from the norm in the liturgy for the circle’s sealing) but still it is nice to see some distinctive elements of our tradition gaining wider recognition.

Besides Feri, in this section Howard also includes material on Pennsylvania Dutch, Pow-Wow, Hexencraft, and Hoodoo, all manifestations of magical craft unique to the New World that carry an inheritance from an old one. Here he does a great service in revealing how these “newer” forms are legitimate inheritors to an older way of practice.

While the book does a wonderful job of compiling many disparate paths and opinions it certainly has its flaws. The editing in this book is horrible, with several typos, mis-numbered chapters, incomplete or incorrectly constructed sentences, inconsistent formatting, and the like. But this is largely what we have come to expect from books of this type as anyone who remembers the travesty of editing that was The Pillars of Tubal-Cain, can attest; another work to which Michael Howard’s name is attached. As someone who has dabbled in self-publishing I can admit to what is often a daunting task as many of my own works have suffered from this very issue. But hopefully the message of this book will be well received and the sloppiness of editing will not detract readers from Howard’s otherwise respectable work.

There is, however, one area in terms of approach in which I feel the author misses the mark. In his dealings with the Feri tradition it becomes clear that the author is drawing from somewhat limited sources and proceeds to “fill in the blanks” with some assumptions of his own. Howard correctly identifies material, such as that from Huna, Voudou, and even the works of modern fiction, that have found home in the rites and philosophical understandings of many Feri practitioners. However he is too quick to assert that the inclusion of this material equates to a deviation from that which comes to us from the Harpy Coven, the traditional witch group that Victor was initiated into as a teen and which modern practitioners of Feri claim initiatory lineage. Howard states:

“This means that the newer groups have deviated from the original teachings of the Andersons that were based on the traditional principles inherited from the old Harpy Coven and representing the Old Craft. In that respect, it is debatable whether they can be classified as traditional witchcraft.”

Whether Feri deserves to be recognized as traditional witchcraft or not is beside the point, but the inconsistency in which the author presents the various groups and traditions is first made apparent here. The assessment that modern Feri groups and practitioners have deviated from our Old Craft inheritance by including newer material is completely lacking of any supportive evidence. It would have been more convincing had he demonstrated how a newer piece of material had supplanted or conflicted with an older one, but we are not given any examples of this. This line of thinking also incorrectly assumes that any of the actual rites, liturgies, and practices of the Feri tradition (modern or not) stem from the Harpy Coven to begin with. As an initiate and a practitioner of Feri for more than 20 years I can honestly say that I have never heard the claim within our traditional circles that anything that we do or what Victor taught were practices based on those from Harpy Coven. To this I say there’s just no there there.

But let’s explore this further. On the surface it would appear to make sense that if a group that received teachings in a traditional form were then to change those forms then they would not be practicing the same tradition. Unfortunately (for this line of thinking) Feri is not a static system; part of the ‘Old Craft’ inheritance that we receive is an ecstatic and ever-changing path that evolves to meet the changing needs of its practitioners, qualities that we will see praised by Howard in other forms of what he recognizes as ‘traditional Craft’, though not for some reason in Feri. While Howard earlier in this work freely admits that contemporary practitioners of traditional witchcraft have often borrowed from other sources (including from modern Wicca) in order to complete the ‘fragmentary rituals’ that they had been passed in their Craft, when it comes to Feri he does not extend this same consideration. This inconsistency of approach is at the heart of why this book is somewhat problematic in its dealings with Feri tradition.

This inconsistency is further highlighted in the chapter on ‘The Sabbatic Craft’. Here Howard presents the workings of the Cultis Sabbati, the work of the late Andrew Chumbley. This form of witchcraft is described to be a mode of praxis wholly created by Chumbley while still presenting itself as a legitimate vehicle for the traditional Craft into which he had been previously inducted. At the core of this tradition is the belief in a sort of astral convocation that is asserted as being the basis for the fantastical medieval depictions of “the Witches Sabbat”; flying astride brooms, taking the form of an animal, dancing around a fire, and orgiastic rites with the Devil himself. In the Cultis Sabbati we are given a picture of a traditional Craft that has beliefs and practices that are handed down in a lineage, but are also “ever changing and being informed by an ongoing praxis.” Howard goes on to say, “It would be wrong to think of modern traditional witchcraft forms as static or totally immersed in the past as they are always evolving and developing to suit changing conditions”. One is left to wonder why this mode of approach was not extended to his view of Feri tradition.

The chapter on the Sabbatic Craft was one of the most enjoyable for me to read. It is obvious that Howard holds Chumbley and his work in very high regard (rightly so!) and he did a beautiful job in presenting it to the reader. I would recommend this chapter especially to those who work in Feri tradition as I found many aspects of Sabbatic Craft as described in this book to deeply resonate with the teachings of Feri both as I received them and as they continually unfold in my work. Its focus on ecstatic workings and trance experiences that form the basis for praxis are of particular note for the Feri practitioner.

In summery, Children of Cain is a respectable and noted addition to the growing genre of traditional witchcraft. While it is not perfect I think it has much to offer both traditional Crafters and modern witches alike.